Do you ever wonder what the ethical ramifications are of offering hope (versus optimism) to others or ourselves when science tells us that the case, the disease, or the condition is not hopeful at all? Well, I do. The use of the word optimism here is both tricky and not interchangeable with the use of the word hope, of course. I thought I knew the difference between hope and optimism very well until I met Mr. D.

***

“Mr. D. is in the emergency room, and the ED paged us to assess him for a potential tracheostomy,” 1 said the person with three pagers clipped to his scrubs, inpatient list extruded from his top pocket about to fall as he ran breathlessly, and a pair of fresh Birkenstocks, telling me about a patient I am all too familiar with. 2 We previously treated him for squamous cell carcinoma of the mandibular gingiva, the gum of the lower jaw. The memory of his surgery remains vivid in my mind as if I had just emerged from the operating room with dried blood on my shoe cover, concealing my ugly, bloody, and old Birkenstocks. I mean, how could I possibly forget the moment we opened his neck? We felt as though a dark cloud momentarily overwhelmed our thoughts. The kind of darkness that resembles a sudden power outage followed by immediate restoration, prompting all of us to exclaim in unison, “Oh boy!” Exposed before us was Stage IVB T4b N2c M0, which signifies an advanced disease that had infiltrated the neck lymph nodes. The tumor had not only invaded the lymph nodes, but had also tethered to the neighboring structures, including muscle fibers, masticator space, part of the hyoid bone, and the internal jugular vein. Yes, yes, that was almost like a radical neck dissection.

In surgery, there is a lot of unspoken language, an internal code, if you will. It manifests when surgeons stretch forth their hands, a subtle plea for the preferring of a pair of scissors, which differs from when they mutely ask for someone to dap to control the bleeding, for example. But at that point, the sight silenced my hands and my voice. Instead, I cast a fleeting glance at my attending surgeon, much akin to how a child earnestly reaches out to their maternal figure in the face of an unexpected situation. And he understood my unspoken thought. He returned my gaze and said, “You have to do what you have to do,” then asked the scrubbed nurse to hand us the Stevens scissors. It was only then that I resorted to the hand language. I opened my right hand to receive the Stevens scissors and my mouth to ask for a Bovie with a Colorado sharp microdissection needle. And we started the surgery, just like that.

Let me tell you, it was a protracted and challenging surgery. We kept peeling, resecting, ablating, cutting, removing, and sacrificing numerous structures during the dissection as the tumor exhibited a vicious nature. Oh, we tried. We strived. We hoped to instill hope to the best of our ability.

The surgery is finished, all right. What is next?

Here is a quick rundown of what we do in our routine practice to monitor our oncology patients following surgery. First, we adhere to a consistent monitoring schedule. During the initial month, we see them on a weekly or biweekly basis. Then, we transition to bimonthly visits throughout the first year. Second, we order baseline computed tomography (CT) scans of the face and neck along with chest CT and laboratory tests to detect any potential new tumors or to follow up on suspicious findings. Third, we consult a lot of people, and I mean a lot of people. We huddle in a place to discuss cases and their management with a team from various specialties. I’m talking about the tumor board, of course. 3

With Mr. D. we encountered a “wait and see” scenario. As with all our oncology patients, we discussed his case with the a-lot-of-people board. Through collective deliberation, we arrived at the decision that the questionable lung nodules had fortunately exhibited stability thus far.

If you believe in science, you would ask, “What are the data points, and what is the prognosis?” If you also happen to believe in hope, you would add, “How hopeful is the case?” Well, what we did was standard of care and scientifically proven measures that cancer centers follow rigorously. For one thing, in conjunction with close monitoring, he underwent radiation therapy and chemotherapy because the final pathology did not yield favorable results, as expected. The tumor exhibited a considerable depth of invasion (DOI), which is a strong prognostic factor according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual. The deeper the tumor (measured from the basement membrane), the worse the prognosis. Now, science tells us three things: (1) if the DOI exceeds 2mm, the failure rate reaches 45.6%; (2) any presence of positive lymph nodes decreases the survival rate by 50%; and (3) any extracapsular extension (ECE), which refers to tumor spread to or beyond the capsule of the lymph node, also reduces the survival rate by 50%. Mr. D. had all three things. “So, it is bad?” Mr. D. asked.

***

In a dimly lit room surrounded by the hum of monitors, I find myself poring over the CT scans of our oncology patients. I spot Mr. D.’s name and scans; both are boldly labeled “CT face and neck – 2 hours ago.” This was a CT we ordered several months after his surgery and is now revealing a disheartening progression of the tumor in various regions of the neck and floor of the mouth. Once again, we present his case to the tumor board, discussing the potential of immunotherapy. Yet, oncologists express limited optimism regarding its effectiveness.

Months later, Mr. D. shows up at the emergency department (ED) with the tumor now impinging on his airway. That is when the resident, with the fresh Birkenstocks, tells me about the ED seeking our consultation for an emergency tracheostomy. 4 The attending surgeon, the resident with the fresh Birkenstocks, and the one with the old and ugly Birkenstocks congregate around the monitor, scrolling through the CT scan slices previously ordered by the ED. “Oh, my!” “That’s bad,” “Oof,” “Yeah, that is really bad,” echoes through my mind.

The sight before us evokes this response. The tumor looms ominously, nearly obstructing the airway. A profound question arises of its own accord: should we proceed with emergency surgery in the operating room, performing a tracheostomy to provide temporary relief? Or should we advise against it? It is a decision that rests in the hands of the patient.

The prevailing argument suggests that a tracheostomy would essentially prolong his suffering, as the pervasive tumor has infiltrated surrounding structures, rendering the tumor not amenable to resection. In essence, this means the patient would have a permanent tracheostomy with a guarded prognosis, 5 as the disease shows no responsiveness to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. And ablative surgery is out of the frying pan and into the fire, for it carries risks that outweigh the benefits. Given these circumstances, what do we tell the patient? The truth, of course. That is the easy question. But I have more questions for you. Should we offer hope? And if so, how much? What are the potential side effects of the offered hope? What damage may be inflicted by instigating hope in cases we know are hopeless?

***

No matter how much training healthcare providers get to deliver bad news to their patients, this process never gets easier. When I find myself in a position of delivering bad news to my patients, my thoughts always wander and land in an unexpected place: Voltaire’s Candide. This novel makes me think twice when I speak optimistically about things. You might ask, “Why care? Speak optimistically and let people be optimistic, anyway.” However, when faced with situations where scientific evidence indicates an unfavorable prognosis, for example, ethical dilemmas arise concerning the balance between offering optimism and embracing realism.

Candide, or Optimism stands as one of the famous works of the French Enlightenment philosopher François-Marie Arouet, AKA Voltaire. In his satirical novel, Voltaire had some beef with the philosophy of optimism adopted by the German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz. This philosophy is epitomized in Leibinz’s theodicy of the "Best of all possible worlds." The narrative, in a nutshell, goes like this: Candide, a young and optimistic individual, was mentored by his professor Pangloss. 6 This professor imparted the philosophy of optimism, positing that everything, even in the face of pure evil, happens for the best. So much so that one may rationalize events as ultimately favorable and accept one’s circumstances without actively striving to ameliorate them, as everything, after all, occurs for the best.

Candide finds himself in a relationship with Cunégonde, the daughter of a baron, taking up residence alongside them in their chateau. However, when the baron finds out about this relationship, he kicks Candide out. Thus commences Candide’s arduous journey, where he faces a myriad of extreme disasters and tribulations, spanning wars, slavery, ca… OK, you can read the novel for yourself. The point is this Cunégonde woman, Candide’s sweetheart, reunites with Candide after he surmounts all the satirical catastrophes, but to his dismay, he discovers that she has become an ugly, narrow-minded, and ill-tempered individual.

I laughed many times when I read it; it is satirical, you know. But also, it is in this Voltaire’s work that I could delineate the boundaries of hope and optimism and explore their intersection. The former can neutralize moments of despair by driving us to take realistic and actionable steps. This is my simple and short answer to anyone asking me about the difference between hope and optimism. Both hope and optimism are based on the notion that every cloud has a silver lining, but hope does so without blinding us to reality and thus allows us to set realistic goals and acknowledge their limits, whereas optimism disregards reality. Hope, much like optimism, offers acceptance as a mindset, but it also offers more than that. It is a mindset conducive to taking action. Thus, hope is reactionary and dynamic, whereas optimism is static and passive. Along with taking steps, hope involves anticipating (and there is so much mental pleasure in anticipation, as described by Socrates), 7 cultivating, resecting, dissecting, undergoing therapy, responding, and reacting to every action whenever feasible.

But to be honest with you, I don’t think arriving at this distinction is helpful anyway. It felt to me that it is only good in the “best possible world,” and maybe in a Cinderella story. Don’t take this the wrong way; I do believe that one should work relentlessly to exhaust all options. Such is the nature of my profession, you see. But let us face it: there exist certain scenarios where all options have been thoroughly exhausted and where the cold hand of science tells us, “Sorry, we can provide you with no more answers at this juncture,” or worse still, “there is no treatment to be had.” In such instances, if hope is reactionary in nature, what course of action should we embark upon? Should we perform the tracheostomy or not?

It was only then that I found my simple and short answer to the difference between hope and optimism to be, like a broken clock, right twice a day. OK, so I know optimism is bad, thanks to Voltaire’s cautionary tale, and hope is good. But also, you can be reactive without being hopeful. You can work relentlessly without being hopeful. You can be realistic without being hopeful. Or can’t you? Is that what hope is all about? Taking actions? There must be more to it. So, I consulted philosophy, other than Voltaire’s Candide, and science.

In philosophical discourse, it is crucial to substantiate the contingencies of why, when, and how hope is offered. But first and foremost, hope is widely regarded as a commendable virtue. In scenarios where the prospect of change appears bleak, hope finds its roots in the soil of epistemic uncertainty. When things are certain, hope serves no purpose. So I swallow and tell myself, “OK, that is it. That is my answer. I must remain hopeful because I must remain virtuous.”

But, but…is that it? Hope makes us err on the side of being reactive, realistic, and virtuous?

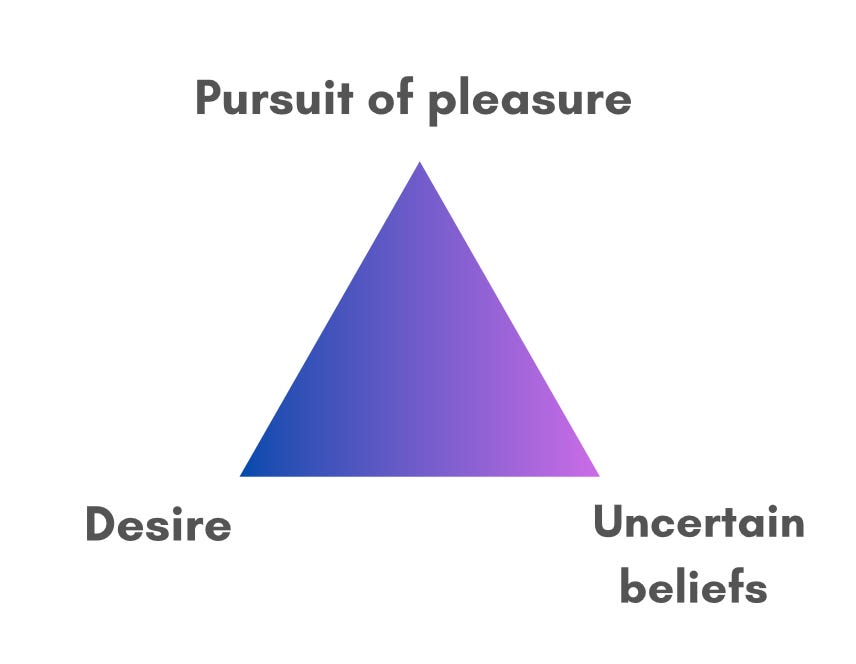

Then I fall on this convoluted concept of hope: when you hope for something to happen or not happen (desire), you feel a bit unsure or in a state of tempered uncertainty (uncertain belief/less confident), but you remain courageous nonetheless and feel excited about the possibility of things unfolding as you desire. In other words, you dare to entertain thoughts of what you ardently desire. And that derives a measure of pleasure, as ascribed by the 17th-century philosophers. “Aha. That is it. That is the carrot,” I told myself. I can now ascertain that hope forms a triangular nexus, entwining desire, uncertain beliefs, and the pursuit of pleasure. But the most important thing is that it grounds itself, as much as possible, in objective reality.

But what do I do with this triangle? You might ask. This trilateral entanglement ought to propel rational cogitation into action, fueling a vigilant mindset that is constantly on the lookout for possibilities and solutions and weighing them with prudence and reason. The act of looking for possibilities, in and of itself, is an action, even when faced with challenging circumstances where things seem dim and grim and all options seem exhausted. Consider, for instance, the decision to abstain from taking action after you have looked for possibilities. In this case, your decision is a deliberate choice born out of thoughtful consideration and pragmatic understanding of the situation rather than a biased judgment of the situation, like that of optimism.

As I ponder the relationship between realism, rationalism, and prudence in conjunction with hope, the following question manifests again: can you be realistic if you rid yourself of hope? The short answer is no. The long answer is in the Contingent Hope Theory. 8 In life-altering events, making the right decision while grappling with a distorted reality can be challenging. But hope allows for the reframing of perspectives and grounding oneself to make a rational decision.

Here is another one. Agency. When you feel you have agency, you assess your situation more realistically and rationally. And what offers a sense of agency? Yes, that is right. It is hope. At least, the American psychologist Rick Snyder seems to think this way. In his article “Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind,” he also draws a distinction between hope and optimism. According to him:

Optimistic goal-directed cognitions are aimed at distancing the person from negative outcomes. Hope theory differs in that the focus is on reaching future positive goal-related outcomes, and there is an explicit emphasis placed on the agency…

Not only do the Contingent Hope Theory researchers and Rick Snyder concur on the linkage between agency and hope, but the notion of agency also emerges as a recurrent motif in the works of both ancient and contemporary philosophers. It serves as a key differentiating factor between hope and optimism. Engaging in wishful thinking or holding onto delusions that shield us from negative realities not only detracts from our ability to rationally analyze events and examine situations but also dilutes our sense of agency.

And here is your cherry on top. Hope improves the quality of life (QoL). I discovered that the significance of offering hope, rather than optimism, to our patients, families, and friends has long been studied, and I am late to the party. Take, for example, a systematic review conducted by Salimi et al. They found a positive correlation between quality of life (QoL) and various factors, hope being among them. All of that is great. What would be even greater is to see an uptrend in both hope and QoL, especially with the advances in science and cutting-edge technology. I can’t speak for others, but I anticipated a commensurate rise in both QoL and hope. It turns out that I was wrong. This very review revealed a decrease in both hope and QoL for cancer patients from 2010 to 2020. Does science render us less hopeful? Does solely believing in science impede our exploration of further scientific discovery and hinder the enhancement of our quality of life?

In my proposition, I posit that the existence of potential confusion between optimism and hope could serve as a plausible explanation for the decline in hope and QoL. The pervasive advertisement for toxic positivity and optimistic outlook within public discourse may have led individuals to mistakenly conflate hope with unflagging positivity and unwavering optimism, resulting in the dismissal of both hope and optimism. It is something that many philosophers have expressed analogous opinions about.

When I first read Camus’ L'étranger (The Stranger), my initial and surface-level reading led me to believe that hope was futile. I equated hope with mere optimism. Sure, my command of French was limited back then, and I was facing major challenges in life. The bottom line is I did mix up hope with optimism. I mean, consider the opening: “Mother died today. Or maybe it was yesterday, I do not know.”

But I read it again in English, then in French, and yet again in French. And I gradually grasped the essence of Camus’s The Stranger. I might still be wrong, and you are welcome to correct me. As for now, the essence appears to be: without hope, life is difficult to live. Hope imparts meaning to life. Maybe this is what subliminally led me to think of hope as a triangle? I still don’t know which facet of the hope triangle provides this profound meaning, or maybe it's all of them.

My working definition of hope is that it serves as a rational compass in contemplating challenging circumstances. It helps guide us toward the silver lining by reflecting upon three fundamental queries:

What are our aspirations and (desires)?

What are the advantages and disadvantages (objective reality) associated with each potential course of action that could bring us closer to these aspirations, bearing in mind that their realization falls under the realm of (uncertain beliefs)?

And, ultimately, what decision should we make?

In this way, we consciously know that we still retain our agency to exercise reasoned judgment while deriving a sense of (pleasure) from the potential outcomes we envision amidst the present situation. However, hope also reminds us that nothing is certain and that not everything unfolds as we expect or desire. Therefore, if these envisioned outcomes do not materialize, as hope teaches us, we can take solace in knowing that we have conscientiously evaluated the situation with a realistic perspective, all else being equal, striving to avoid both overly melancholic perspective and unwarranted optimism.

So, en retour de our question: What are the ethical ramifications of offering hope (as opposed to mere optimism) to others or ourselves when science tells us that the case, the disease, or the condition is not at all hopeful? The answer to this quandary remains intricate. But, if hope empowers individuals with greater agency, improves decision-making, and enhances the quality of life, then is it ethical to deprive patients of hope?

I witnessed many physicians during residency prematurely giving up on their patients because science seemed hopeless. Conversely, I also witnessed many cases that seemed hopeless, yet both physicians and family members clung steadfastly to the beacon of hope, and patients turned the corner.

When we relinquish hope, our ability to assist others and ourselves becomes undermined. We give up on our patients when alternative options may have been obscured by despair. It is hope that gives us the impetus to break the world's records. It is hope that helps us strategize to get out of imminent checkmate situations. It is hope that makes a good, compassionate, and caring physician. It is hope that provides solace and support to patients in somber moments.

One of hope’s remarkable attributes lies in its ability to instill belief, and we need to believe to effect meaningful change.

The most important scene in the novel is when Candide encounters a Muslim Turk 9 who worries about nothing but cultivating his own garden alongside his family. His famous saying “Il faut cultiver notre jardin,” which translates to "We must cultivate our garden," resonates deeply with Candide. It is at this juncture that he realizes that he got it all wrong and that, had he abandoned optimism, he could have spared himself numerous unnecessary battles. Voltaire’s adage has sparked various philosophical debates, yet one interpretation underscores the essence of hope: to realistically and rationally evaluate our world and our gardens, cultivate what lies within our reach, and tend to what is within our control. If we can rid ourselves of utopian ideology and optimism, we can overcome hurdles realistically and pragmatically, recognize the power of our own agency, and lead fulfilling lives. Now, let us revisit the pressing question: should we perform the tracheostomy?

Mr. D. has been duly informed that the tracheostomy would temporarily assist his breathing, but unfortunately, the tumor is not operable, for it has metastasized. “How much do I have?” he asked. The truth is no one knows with absolute certainty. However, based on the tumor’s progression rate and since it has engulfed vital structures, the estimated timeframe could range from days to months. “I want to say my goodbyes to my people,” he said, “so I wish to proceed with the emergency tracheostomy.” We performed the tracheostomy and consulted palliative care to alleviate his pain and ensure peaceful passing.

If hope stimulates us to cultivate our gardens, to lead a fulfilling life guided by balanced desires and pleasures, and to achieve remarkable feats, the ultimate and crucial two questions arise: Where does the joie de vivre lie if we forfeit the plaisir of anticipation? And what makes us alive and keeps us going?

I don’t know about you, but this French saying strikes me deeply every time I read it: L’espoire fait vivre.

Please note that storied data on this blog adhere to privacy laws and regulations.

For those of you who are not knee-deep in the world of medicine, let me introduce you to my junior resident. “Enchanté,” he says.

A multidisciplinary team of experts (a lot of people) comprising radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, head and neck surgeons from various specialties such as oral and maxillofacial surgeons and ear, nose, and throat surgeons, as well as cancer unit coordinators, and speech-language pathologists.

A surgical airway to create an opening in the trachea to alleviate the obstruction.

I’ve got a certain distaste for this term. But what really rubs me the wrong way is employing it when dealing with patients. To start, it’s a lousy term for effective communication since it can convey a heap of meanings, leaving patients utterly clueless about its true intent. Also, even amongst healthcare providers, this can mean there needs to be more information to tell what the prognosis will be. But it can also mean that the prognosis is grimmer than poor, as in the patient being on the brink of no return. And that is the common use of this term. Instead of opting for candid, clear, and empathetic communication with patients, I hear this term being trotted out with patients to simply dodge having an honest conversation.

Not-so-very reliable sources say that Pangloss is the amalgamation of Pan + Gloss = All gloss/shiny. Conversely, Encyclopedia Britannica and many JSTOR articles say that “Gloss” in Pangloss harks back to its ancient Greek etymon “glōssa,” denoting tongue, just like we use it in medicine. Thus, the use of Pangloss alludes to loquaciousness. Either way, quite clever, Voltaire!

Hope and pleasure as the “pleasures of anticipation”

One facet of the hope triangle resides in uncertain belief, as highlighted in the Contingent Hope Theory study by Currin-McCulloch et al. This study explores the role of hope in navigating the uncertainties of life faced by young adults diagnosed with advanced stage cancers. The contingent hope cycle, along with its psychosocial processes, offers an explanation for the role of hope in the decision-making process and the rational assessment of the risks and benefits associated with any offered treatment.

Among Muslims, the concept of hope doesn’t mean staying idle, yet it doesn’t solely hinge upon individual effort either. It entails a calibration between advancing one’s aspirations while humbly recognizing the sovereignty of divine providence. If it’s meant to be, it will be. Emphasis is placed on navigating what’s within reach. It spurns naive optimism or “pseudo-hope.”

Dear Razan,

"One of hope’s remarkable attributes lies in its ability to instill belief, and we need to believe to effect meaningful change."

Thank you for this smart and thoughtful post.

Curious how you feel about these two questions:

- What role do you feel the depth of one's belief plays?

- What role do you feel faith plays here?

Humbly,

Rodrigo

Loved chatting about books with you last night & bookmarked this for my morning coffee - a great read! Thanks for sending me into my day ahead full of hope <3